What is Ranked Choice Voting (RCV)? It’s all in the name. Instead of voting for a single candidate, you rank the candidates in your preference. If your first choice does not have enough votes to win, your vote passes to your second choice (and so on). Why is RCV good? Here are two reasons. First, only a candidate with a majority of votes will win. We have seen countless times a candidate with nowhere near a majority of the votes win just because they had the more than the other candidates. In RCV, voting goes in rounds, eliminating candidates until one has over 50% of the votes. This way the majority of a district truly get a representative that they want (even if he or she is not their first choice). The second benefit is that voters no longer have to play games and vote strategically. They can vote for any small party they want without fear of “wasting” their vote. For example, if you believe the Libertarian Party represents your views, you may vote for the Republican candidate just because you don’t think the Libertarian will win. Under RCV, you can place your first vote for the Libertarian and your second for the Republican (and a 3rd and 4th candidate, etc…). This way your voice is still heard, even if your primary choice is eliminated through the rounds of voting. This is sufficient for single-seat elections, such as the president or governor. In councils or legislatures which have multiple winners, we can improve on RCV by including proportional representation.

Note: In some countries, RCV is known as instant-runoff.

Proportional representation is a name for any system that tries to accurately reflect the choices of the people. Let’s say state sends 10 people to the House of Representatives. If 50% of people in the state vote for party A, 30% vote for party B, and 20% for party C, then the House should have 5 representatives from party A, 3 from party B, and 2 from party C. Today, we have districts that send a single member to Congress. In our example state, there would be 10 districts. If each district reflected the state’s average, meaning each district has 50% of the votes for party A, then party A wins each district. That means the state will have 10 members from party A, and the people who voted for Party B and C (half of the state) have no representation. This is not a democratic system.

One solution to this is to use multi-member districts. When we combine RCV with multi-member districts, it is called Proportional RCV (P-RCV), or in some countries Single Transferable Vote (SVT). This process can sound confusing at first, but it is pretty straightforward. Let’s split our state into two districts of 4 members and a district of 2 members. The limit to win in a district is 100% divided by the number of seats. In the 4 seat district, the candidates need 25% to win. In the 2 member, 50%. In our example, each district will have 6 candidates trying to get a seat.

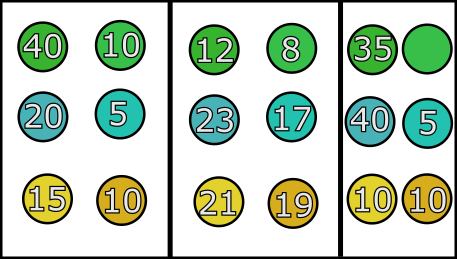

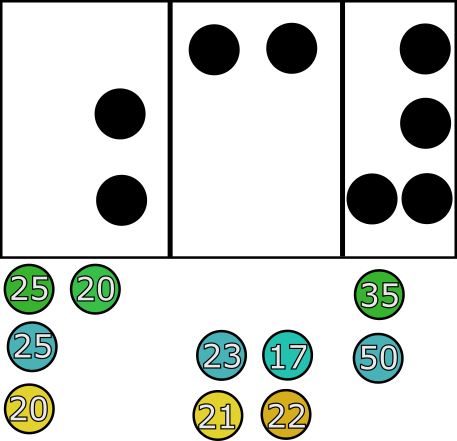

Look at the images below. Each circle is a candidate and the number is their percentage of votes. Each rectangle is a district. In our 1st district, Green A has 40% and is a winner. Nobody else in any district has hit the percentage to win, so the lowest is eliminated. Cyan B loses in the 1st, Green B loses in the 2nd and 3rd districts.

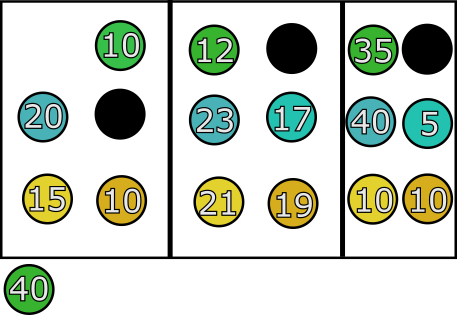

The voters for the eliminated candidates do not lose their votes. They ranked their choices, so their vote goes to their second choice. Additionally, the surplus votes for the 1st District’s Green A are not thrown away. The surplus votes also go to the second choice.

What are surplus votes? Votes that put a candidate beyond the threshold are considered surplus. Surplus redistribution is another method for removing the need to vote strategically. With surplus redistribution, voters are not punished for voting for a popular candidate. Surplus distribution should be done before elimination. Let's say two members of the most popular party are running, but one candidate is much more likable and takes all the votes. This would allow the second candidate to be elimanted and allow less popular candidates to take more seats. That would be lead to an inaccurate representation.

There are various methods to determine how surplus is transferred. A good way is to use the percentages based on the distribution of the second choices. If 2/3 of District 1's Green A’s voters choose Green B as a seoncd choice and 1/3 chose Yellow, then the excess votes would spread that way. We have 15% surplus, so 10% (2/3 of 15%) go to Green B and 5% (1/3 of 15%) go to Yellow. This brings both Green B to 20% and Yellow, still shy of the threshold.

Now the eliminated candidates. In the 1st District, everyone who voted Cyan B chose Cyan A as their second choice. Cyan A now has 25% and is a winner. In the 2nd District, Green B’s voters are not partisan. The 8% of the vote Green B received will be redistributed to the second choices: 2% go to Green A, 3% go to Cyan B, and 3% go to Orange. In the smaller 3rd district, no one voted for Green B. The next round in the 3rd district eliminates Cyan B. The 5% of the vote Cyan B received transfers: 4% to Cyan A and 1% to Orange. We still have no winners in the 2nd and 3rd districts.

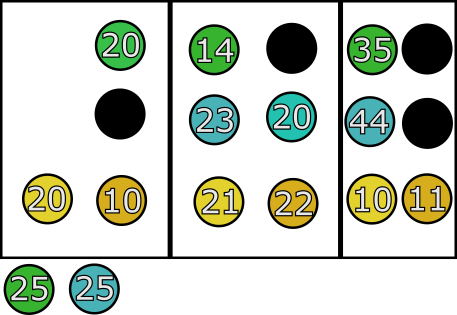

Next round. In the 1st District, Orange is eliminated. There are now 4 candidates for 4 seats, so Yellow and Green B are elected. In the 2nd District, Green A is eliminated. Again, 4 candidates and 4 seats, so all 4 are elected. There is no need to redistribute votes if we have no excess candidates. In the 3rd District, Yellow is eliminated, transfering its 10% of the vote: 6% to Cyan A and 4% to Orange. This gives Cyan A enough votes to win.

Orange is then eliminated and Green A elected by default.

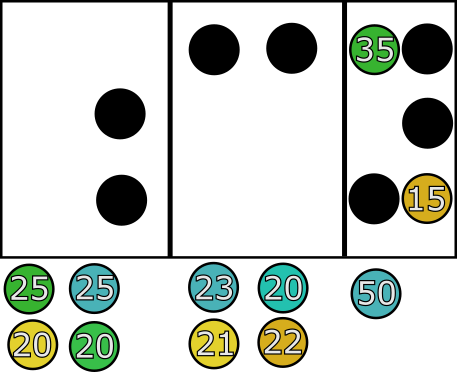

Let’s look at the results. We have 3 Greens, 4 Cyans, 2 Yellows and an Orange. If we count the first choices across all of our districts, Green has 35%, Cyan has 36.7%, Yellow has 15.3%, and Orange has 13%. In our elected legislature, Green has 30% of the seats, while Cyan has 40%, Yellow has 20%, and Orange has 10%. Since we only get 10 seats, a change in the legislature can only occur in 10% increments. Given that limitation, this is close representation of the actual views of the population of our imaginary state.

Why do we bother with districts in the first place? Why not have our state be one big district? It seems the reason is that people just prefer districts and more local candidates. The district could be made as big as people will tolerate. H.R.3863 - The Fair Representation Act – would use districts of 3-5 members. This is the system that Ireland uses today in their lower chamber.

This is not the only system, but it’s the one I like best. Every voter has their voice heard and it eliminates many problems the American system has today. The concepts of spoilers and wasted votes are gone. Minority rule is gone and the winners are guaranteed to a certain backing by the populace. With multi-member districts, we can make the representation a much closer match to voter’s actual views. What are we waiting for?

Updated 11/8/23